IFN-? deficient macrophages taken from patients with cystic fibrosis that were then infected with the bacteria Burkholderia cenocepacia and treated with synthetic IFN-? were found to have enhanced autophagy, which weakened the bacterial infection. The process could help clear a lethal bacterial infection in CF, according to a new study published in PLoS One by researchers from The Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

Produced by the IFNG gene in humans, IFN-? is a cytokine active in the immune system. Studies have suggested that the molecule stimulates autophagy, a natural process in which proteins and other cell materials are degraded and disposed. In many diseases, including cystic fibrosis, autophagy is inhibited.

In people with CF, cells that line the passageways of the lungs, pancreas and other organs produce unusually thick and sticky mucus that clogs the airways, which creates an ideal environment for pathogens such as B. cenocepacia.

B. cenocepacia is commonly found in soil and water and in most cases poses no health threat. However, in 2% to 5% of patients with CF, the bacterium causes an infection that can spread to the bloodstream, triggering widespread inflammation called sepsis that can be fatal. B. cenocepacia doesn’t respond to most antibiotics, leaving physicians with few weapons to fight it. And even if their infection isn’t severe, patients with B. cenocepacia are considered poor candidates for lung transplant, which many advanced CF patients require to survive.

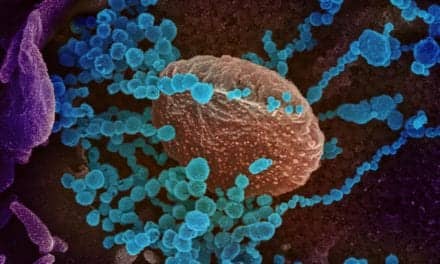

As part of the study, researchers isolated macrophages from patients with and without CF and infected these microphages with B. cenocepacia in cell cultures.

When researchers analyzed the samples, they found that the cells from CF patients had decreased levels of IFN-?. They then treated the CF macrophages with synthetic IFN-? and found that autophagy was enhanced and the bacterial infection waned.

“The goal of the study was to show if you could stimulate autophagy, you could help clear pathogens better,” said Benjamin T. Kopp, MD, senior author of the study and a principal investigator for the Center for Microbial Pathogenesis and a pulmonologist at Nationwide Children’s. “These findings clearly suggest that is indeed the case.”

B. cenocepacia doesn’t respond to most antibiotics, leaving physicians with few weapons to fight it. And even if their infection isn’t severe, patients with B. cenocepacia are considered poor candidates for lung transplant, which many advanced CF patients require to survive.

“B. cenocepacia is multi-drug resistant, so usually when patients are ill, they are on a cocktail of antibiotics and we’re hoping for a synergy of effect,” said Kopp, who also is an assistant professor of pediatrics at The Ohio State University College of Medicine.

Further complicating these infections, Kopp added, is that B. cenocepacia can replicate inside macrophages, the immune system’s first line of defense against such pathogens. “It can avoid the host immune response,” he said, “and that’s where something like IFN-? might work better than traditional antibiotics.”

The study is the first in a series by Kopp and colleagues to look at autophagy mediation, a growing area of interest among clinician scientists who study CF and other disorders that affect the immune system. In CF, the need for new treatments is great. Many of the infections that plague this patient population are resistant to available drugs and some of the drugs that do work have side effects that leave many physicians unwilling to prescribe them.

“As we’re learning more about CF, we’re finding more and more issues with the immune system and not just the typical clearance of mucus,” Kopp said. “Now we’re discovering that there is this initial response, of which autophagy is a part, in which the immune system is not clearing the bacteria and there are some continued deficits in that in CF patients.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, B. cenocepacia infections have also been reported in hospitalized patients with compromised immune systems. So, Kopp added, the findings could be of interest to clinician-scientists in areas other than cystic fibrosis.