Here are five valuable tips to achieve reliable, accurate results when performing spirometry tests to diagnose or manage COPD.

By Bill Pruitt, MBA, RRT, CPFT, FAARC

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the top three causes of death world-wide but remains a treatable and preventable disease. It is characterized by unrelenting symptoms (cough with or without sputum production, dyspnea) and reduction in expiratory airflow.1

Smoking tobacco is the main risk factor but COPD can also be caused by exposure to air pollution, biomass fuels (i.e. heating or cooking by burning organic materials), or due to genetic factors (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency). For patients who have symptoms and increased risk (through exposure or genetics), spirometry is required to make a diagnosis.1 From the American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines, “Spirometry is a physiological test that measures the maximal volume of air that an individual can inspire and expire with maximal effort. The primary signal measured in spirometry is either volume or flow as a function of time.”2

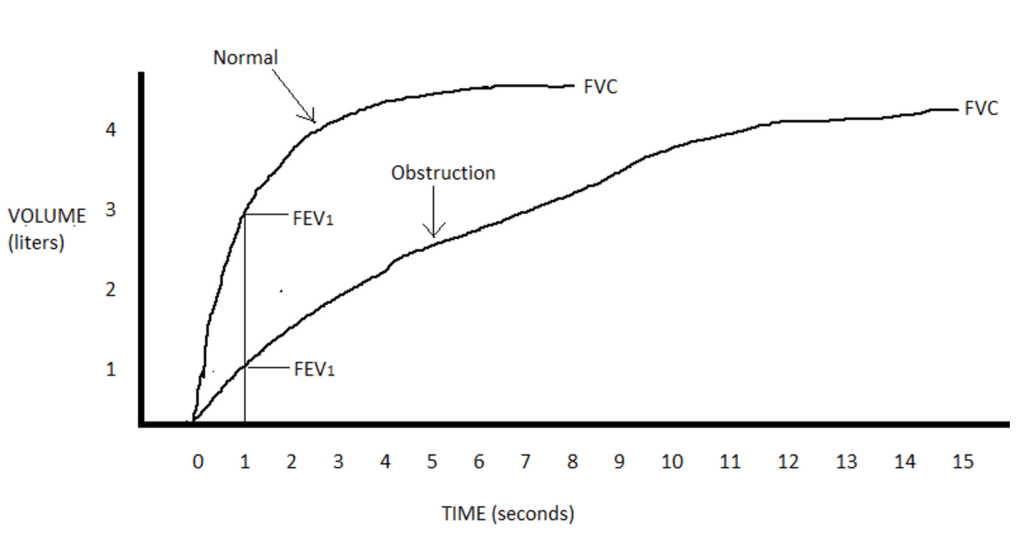

The main two measurements in spirometry are the FEV1 and the FVC. FEV1 is the forced expiratory volume measured in the first second of the maneuver, starting from a maximal inspiration. FVC is the forced vital capacity, measuring the maximum volume of exhaled air in the maneuver after the maximal inspiration and is measured along with the FEV1 (several other measurements are also gathered during the test). Post-bronchodilator results showing a FEV1/FVC < 70% in symptomatic patients confirms the presences of persistent airflow obstruction and establishes the diagnosis of COPD.1-2

When performing spirometry tests with patients to look for possible COPD or to help manage the disease in those with confirmed COPD, here are some valuable tips to keep in mind to achieve reliable, accurate results.

1. Calibrate the Spirometer Daily and Use Care in Performing Infection Control Practices for Devices, Staff, and Patient

Spirometry calibration should be performed according to the American Thoracic Society guidelines (See reference 2). Infection control activities have been enhanced in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and should follow guidelines such as those published the European Respiratory Journal and from the ATS.3-4

2. Have a Detailed Medical History and Physical Exam

The medical history should check for exposure to risk factors, patterns of exacerbations, emergency department visits/hospitalizations, review of symptoms, family history, comorbid conditions, and what treatments, if any, have been utilized. The physical exam should be thorough with careful attention paid to the cardiopulmonary systems. Since predicted values are based on age, height, and birth sex, these factors must be checked and entered into the PFT device (with considerations for race/ethnicity). Birth sex (not gender or gender identity is used in determining the correct predicted values. Finally, be aware that spirometry is physically demanding and there are some relative contraindications for performing the test (see reference 2).

3. Patient Preparation

Patients should have some understanding of what the test entails with encouragement to do their best and give maximum effort during the testing. If the spirometry is being done to determine if the patient has COPD or to get a baseline measurement, certain medications should be withheld (ie, short and long-acting bronchodilators) to obtain a pre-bronchodilator test. The guidelines state that there is no need to withhold inhaled corticosteroids and leukotriene modifiers. The patient should also wear comfortable, loose fitting clothing, and keep their dentures in place during the testing (if they are well-fitted).2

4. Coaching and Patience

Good coaching, patient cooperation/performance, and patience are the keys to getting a quality test. If possible, have the patient view a video or provide a demonstration of the maneuver prior to testing so the patient will understand the actions and see the effort needed. Use verbal encouragement (“Deep breath, Blast out, Keep blowing, You’re doing good, Keep blowing, Don’t stop”) throughout the test. The goal is to elicit maximal effort for quick, full inspiration, forced expiration, and final quick, full inspiration. A minimum of three recordings (with a recommended maximum of eight) is needed — feedback on the performance can help improve or maintain the actions needed to get the best results.5

Timing is important to achieve a good start of FVC performance and continuing the expiratory effort to reach the end of test (end of expiration) criteria. The tester’s body language can also help in encouraging an acceptable test. Enthusiastic coaching that is direct, quick, and supported by the tester’s body language can help get a good patient effort — as opposed to quiet, passive instruction with little or no body language/actions. Shouting is not needed, but focused enthusiasm helps in motivating the patient.

There are four parts to the FVC performance:

- A rapid, maximal inspiration to reach total lung capacity (TLC)

- A very brief pause followed by a forceful “blast” to begin expiration

- Continued full expiration (usually for at least 6 seconds and nor more than 15 seconds)

- Rapid inspiration back to the maximal lung volume (TLC).

- Most problems in testing relate to inadequate and variable inspiration in part 1, stopping the expiration too soon in part 3, or variable effort in any part.2

These four parts are unnatural and may be uncomfortable for the patient. Depending on the severity of the disease, COPD patients may have a very reduced expiratory flow and prolong expiration that causes more discomfort when trying to perform this maneuver. Be aware that these maneuvers can bring on a syncopal episode — watch the patient and be prepared to prevent a fall if syncope occurs. Feedback between each maneuver is needed to correct issues. Explain what is needed to fix a problem area while giving praise for what was done correctly. Finally, patients often need time to recover between maneuvers so the tester needs to allow for this by having patience — do not rush through the process but wait until the patient says they are ready to go forward. This is a physically demanding test involving unnatural breathing patterns and requires patient cooperation and performance.

Here is an example of the instructions used to explain the test to the patient:

“Please start with normal breathing. Then I want you to take a huge breath in until your lungs are completely full, and blast it out as hard and as fast as you can until you feel you are completely empty and cannot blow out further. Then I want you to take another big, fast, full breath in.”5

5. Evaluation of the Tests, Patient Effort

Each maneuver should be technically acceptable, clinically usable, and repeatable. These criteria are defined by ATS standards and include several particulars. Sometimes a maneuver may not be acceptable but if the patient is doing the best they can, the maneuver may be clinically useful. Some examples of these standards include a good start of expiration reflected in an acceptable back-extrapolated volume (BEV), no cough or glottis closure during the first second of exhalation, evidence that end of forced exhalation is achieved (ie, acceptable expiratory plateau), and no leak around the mouthpiece. (See details in Table 7 from reference 2).

In evaluation of part 4 (mentioned above), the forced inspiratory volume should match the FVC. If the forced inspiratory volume is greater than the FVC, the patient did not start expiration at TLC. A maneuver where the forced inspiratory volume is > 100 mL or 5% of the FVC is not acceptable. Results are reported in numerical values and in graphic form. (See Table 2 for examples of volume-time curves and flow-volume loops for normal compared to obstructive disease results.)

For both pre and post-bronchodilator tests, the object is to record a minimum of three acceptable FEV1 and three acceptable FVC measurements but they do not necessarily need to be from the same maneuver. The FEV1 is acceptable (and repeatable) if the largest and next largest value is <150 mL. The same criteria (<150 mL) is used for the FVC measurements.

For some patients, the FEV6 may be used in reporting rather than the FVC. This is particularly useful with patients who have a very prolonged expiration due to low airflow — some patients can “blow out” for 15-20 seconds (or more) before reaching the end of expiration criteria, and/or they may not be able to reach the end of expiration before stopping spontaneously. In these cases, the advantages for using the FEV6 that the FEV6 is more reproducible, less physically demanding for certain patients, has less risk for causing syncope, and it provides a more explicit “end of forced expiration”. 2 The ATS 2019 update for spirometry provides a guide for grading the spirometry results for repeatability. (See Table 1 below for details.)

Table 1. Grading System for FEV1 and FVC for both pre- and post-bronchodilator studies

| Grade | Number of measurements | Repeatability (for ages >6 yrs) |

| A | > 3 acceptable | Results within 150 mL (best and next best) |

| B | 2 acceptable | Within 150 mL |

| C | > 2 acceptable | Within 200 mL |

| D | > 2 acceptable | Within 250 mL |

| E | > 2 acceptable OR 1 acceptable | > 250 mL (N/A if 1 is acceptable) |

| U | 0 acceptable AND > 1 usable | N/A |

| F | 0 acceptable and 0 usable | N/A |

Conclusion

Spirometry testing provides objective data that can help make a diagnosis of COPD and help in the management of COPD. It is a challenging test for both the tester and the patient, with several particular and unusual activities that must be done in a timely fashion.

The guidelines for performing spirometry are detailed and specific, and the tester must understand them and know how to coach a patient to correct any issues. Results need to be acceptable, clinically useful, and repeatable results, and testing should be safe for patients and staff while obtaining accurate measurements. For the tester, experience over time can help sharpen the skills needed for good testing. For the COPD patient, this test may be one that they must perform several times during the course of their disease. Having good support and coaching, with efficient efforts from the tester, can help the patient perform the test effectively.

RT

Bill Pruitt, MBA, RRT, CPFT, FAARC, is a writer, lecturer, and consultant. He has over 40 years of experience in respiratory care, and has over 20 years teaching at the University of South Alabama in Cardiorespiratory Care. Now retired from teaching, he continues to provide guest lectures and write.

References

- From the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2022 Report: https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/. Accessed 10/5/2022.

- Graham BL, Steenbruggen I, Miller MR, Barjaktarevic IZ, Cooper BG, et al. Standardization of spirometry 2019 update. An official American thoracic society and European respiratory society technical statement. Am J Resp Crit care. 2019 Oct 15;200(8):e70-88.

- McGowan A, Laveneziana P, Bayat S, Beydon N, Boros PW, et al. International consensus on lung function testing during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. ERJ open research. 2022 Jan 1;8(1).

- From the American Thoracic Society. Pulmonary function laboratories: advice regarding COVID-19. https://www.thoracic.org/professionals/clinical-resources/disease-related-resources/pulmonary-function-laboratories.php. Accessed 10/4/2022.

- Cheung HJ, Cheung L. Coaching patients during pulmonary function testing: A practical guide. Canadian Journal of Respiratory Therapy: CJRT= Revue Canadienne de la Thérapie Respiratoire: RCTR. 2015;51(3):65.

Table 2. Examples of Spirometry Results (Volume-time Curves and Flow-volume Loops)

A. Both tests reached a similar FVC (just over 4 liters) but the obstructed tracing has a much slower expiratory flow and a reduced FEV1 (normal is at 3 liters, obstruction is at 1 liter). Expiratory time is much different to reach end of expiration (normal is at 7 seconds, obstruction is at 15 seconds). The final inspiration after full expiration is not shown in this tracing.

B. Forced expiration is found above the horizontal line and the final full inspiration is below the horizontal line. Both tests reached the FVC (just over 4 liters) but the expiratory and inspiratory flow in the obstruction case is greatly reduced.